Let’s dance!

We want to know all about how proteins “dance” in the crystal. In addition to having their own individual moves (see the DaVinci Dude Dance post), different proteins can’t occupy the same space at the same time, and sense and respond to their neighbors, even at a distance.

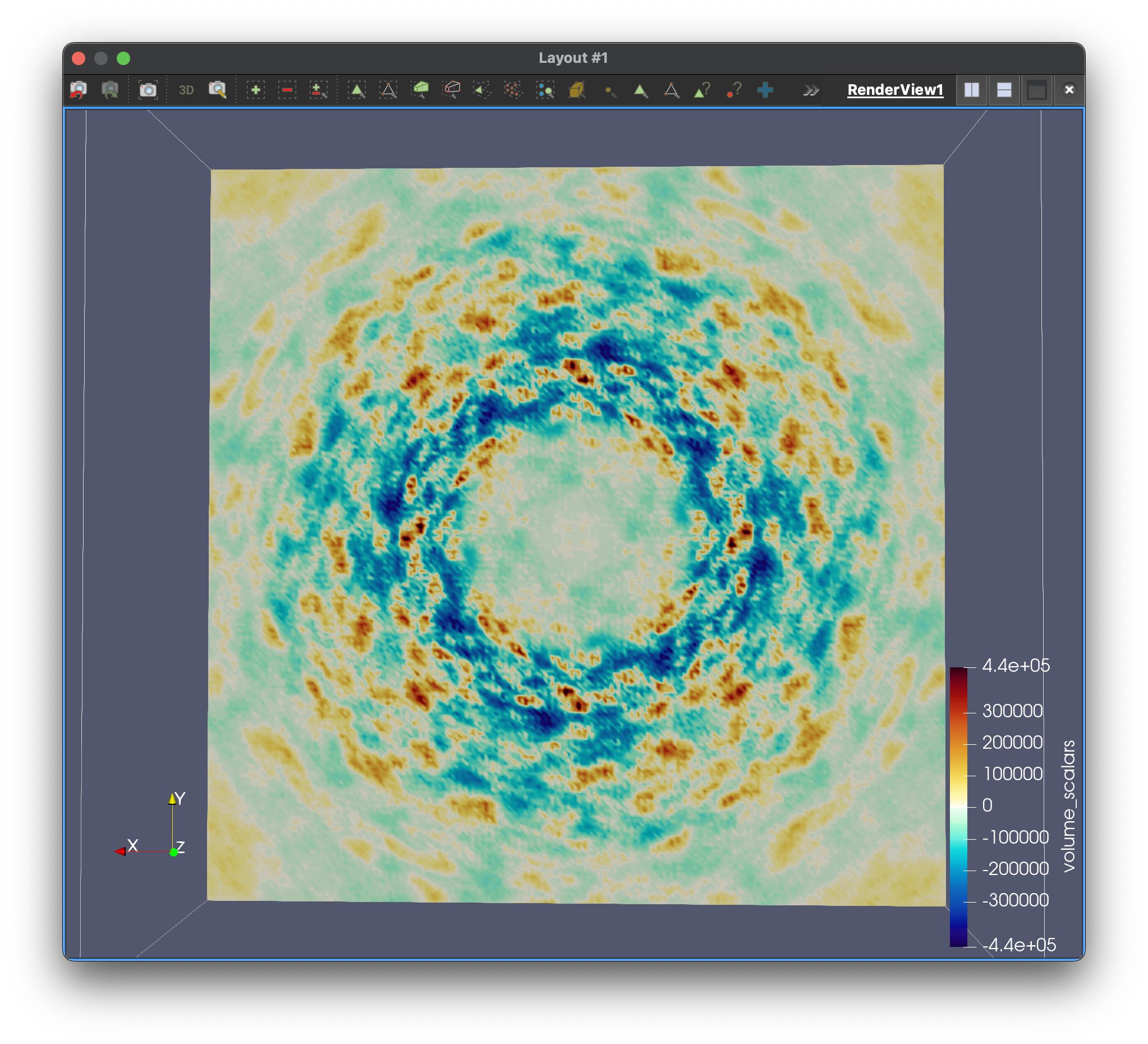

Molecular-dynamics simulations give us a picture of the whole choreography. Starting with the crystal structure, our simulations evolve using assumptions about the underlying physics. The motions appear random but follow patterns that show up in the diffraction. Right now researchers can make molecular-dynamics simulations agree reasonably well with the diffraction data, but the agreement isn’t perfect. In particular, so far the simulations haven’t done a very good job of modeling both the Bragg and diffuse data simultaneously.

We’re working to fix this problem.

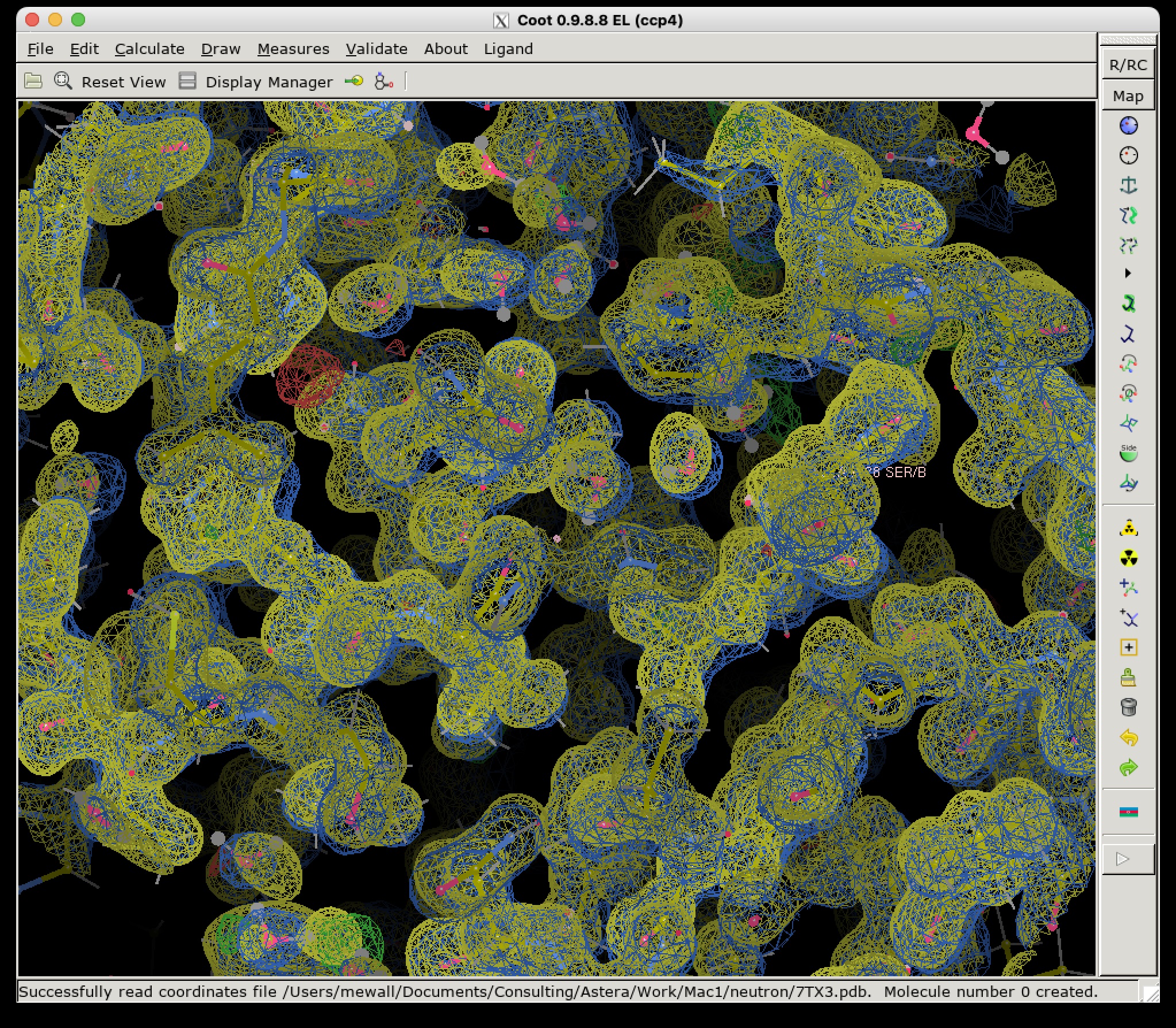

Our first simulations are especially important, as they’ll serve as a reference to assess our progress. Inspired by the project’s first experiments during the diffUSE kickoff meeting (see Getting our feet wet post), we’re performing simulations of SARS-Cov-2 Nsp3 macrodomain, the subject of a beautiful neutron crystallography study done in the Fraser lab.

Above is a first look at the initial results. In the movie, the waters look like swarming gnats, the ions are balls, and the proteins are cartoon ribbons. The proteins wave around and also jostle their neighbors. Waters and ions diffuse and sometimes stick to the protein for a while.

The simulated electron density in the center panel shows the average picture. It doesn’t give us information about how atoms move together, but diffuse scattering does (right panel). Combining both will enable us to develop more accurate MD models of protein crystals.

Methods

The lunus repository has some examples of how to prepare crystalline MD simulations and use them to analyze Bragg and diffuse data.