Taylor’s Diffuse Rotation

An Atypical PhD Start for an Atypical Student in Biophysics

I walked into Jaime Fraser’s office on a Friday in June, shortly before my early summer rotation at UCSF was about to start. As a physicist by training, I found his work on conformational entropy in proteins fascinating. But he quickly turned our conversation towards a topic I had never heard of before: diffuse X-Ray crystallography and somehow using it to solve protein ensembles and dynamics. “We’re kicking off the initiative at a conference on Monday, you should come!”

Come I did. While I was very lost on the specifics of most of the science during those two days, I could sense the excitement. Whole labs had traveled from across the country to attend as well as esteemed scientists from more than one national laboratory. They were proposing a new way to do science, more open, more flexible, and faster than we have come to expect from the traditional academy. So I did what any 1st-year PhD student would given the opportunity to join such a project, I took it and ran with it.

There was one small problem with joining a structural biology lab on the pretense of innovating in the theory of X-Ray crystallography during a summer rotation: I hadn’t touched diffraction since my bachelor’s degree. I too was coming off the heels of a master’s degree at Utrecht University and a follow-up internship at the University of Vienna both in theoretical physics. So I started at the beginning.

I was already reading the basics of Thomson scattering of a free electron before the end of day 2 at the diffUSE kick-off conference. “OH, it’s just the oscillation of the electron under electromagnetic radiation that emits scattered rays of the same frequency”. I’m not sure why but I always expected there to be a lot more quantum mechanics involved in scattering. As is often the case, the classical understanding of even very small systems is very much good enough.

The beginning of my rotation was nose to the grind stone in the form of review papers and textbooks, including some from the middle of the last century. I needed to understand classical structural X-Ray crystallography before I even knew how to ask Jaime what diffuse X-Ray crystallography is. Finally, after a few weeks, I knew what a Bragg peak and a structure factor were, and I had actually worked through the derivation of what I consider the central result of crystallographic theory: the electron density of the unit cell (and therefore the molecular structure of the contents of the unit cell) is the Fourier Transform of the scattered structure factors in diffraction space (and vice versa!) So what about diffuse?

Example scattering image (right) from a perfect crystal (left) with 6-atom hexagonal molecules at each lattice site. Structural information is contained in the sharp reflections (referred to as Bragg Peaks) of the scattered X-Rays. The scattering imafe is devoid of diffuse scattering. Fig. 5.5, Blundell and Johnson (1976).

Example scattering image (right) from a perfect crystal (left) with 6-atom hexagonal molecules at each lattice site. Structural information is contained in the sharp reflections (referred to as Bragg Peaks) of the scattered X-Rays. The scattering imafe is devoid of diffuse scattering. Fig. 5.5, Blundell and Johnson (1976).

diffUSE X-Ray Scattering

Now this central tenant is only 100% correct if each unit cell of a crystal is identical, but as every structural biologist knows, it is nigh impossible for a molecule as complicated as a protein to crystallize into the exact same form in each and every unit cell throughout a crystal. Besides the possibility of ligand-bound complexes, the protein itself can be in subtlely different folds between each unit cell. These are known as the protein’s conformers, and they result from small adjustments to a protein’s structure like bond rotations. All of the conformers available to a protein are known as its ensemble.

So do Bragg peaks still give you the protein structure when all different kinds of conformers might be present in a protein crystal? Yes and no - the structure you get from analyzing the scattering pattern is the averaged structure due to the averaged structure factors between all the unit cells. Yet the signal is not actually the same as if every unit cell were replaced with this averaged structure; the fact that the crystal is composed of different conformers is encoded in the scattering image as an unphased diffuse signal between the Bragg peaks.

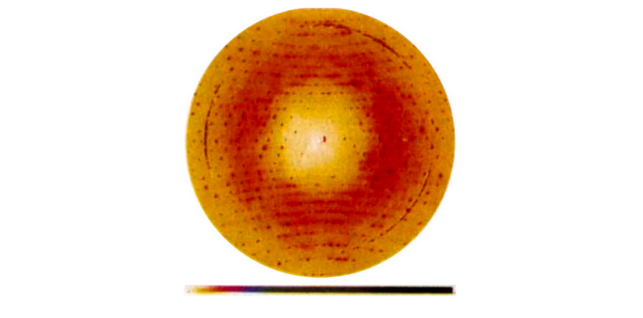

X-Ray scattering image of insulin. The signal between the sharp Bragg peaks is the diffuse scattering. The isotropic ring is due to water’s presence in the crystal as a solvent, but non-isotropic diffuse signal is due in part to insulin’s conformational ensemble. Meisberger and Ando (2023).

X-Ray scattering image of insulin. The signal between the sharp Bragg peaks is the diffuse scattering. The isotropic ring is due to water’s presence in the crystal as a solvent, but non-isotropic diffuse signal is due in part to insulin’s conformational ensemble. Meisberger and Ando (2023).

The dominant term contributing to this diffuse signal is known as Guinier’s Equation:

\[I_{\text{diffuse}}=I_{avg}-|F_{avg}|^2\]$I$ is the intensity reading on the detector and $F$ is the complex structure factor. These values are averaged (a phased average in the case of the structure factor) over each and every unit cell at each spot on the X-Ray detector. If each unit cell is truly identical, then the average intensity is the same as the square of the average structure factor and the diffuse signal is exactly zero. Now if you have ever learned that the intensity is the complex square of the structure factor, then you can see Guinier’s Equation in a new light (transitioning to the angle brackets notation for ensemble averages):

\[I_{\text{diffuse}}=<|F|^2>-|<F>|^2\]The diffuse signal is really the statistical variance in the structure factor over every unit cell. James Holton, an expert beamline scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, has a great interpretation of this variance up on his blog: the diffuse signal allows you to differentiate between correlated motions of the crystal’s unit cells. Now if we determine the correlated motions between the various conformers of a protein, we are really solving for the available dynamics of that protein! This is what makes diffuse protein X-Ray crystallography a big deal, and what the diffUSE initiative aims to accomplish. Much of protein behavior requires dynamics: catalysis, bond formation, active transport - solving the diffuse problem will allow for a whole new insight into the correlated dynamics that allow proteins to perform their functions.

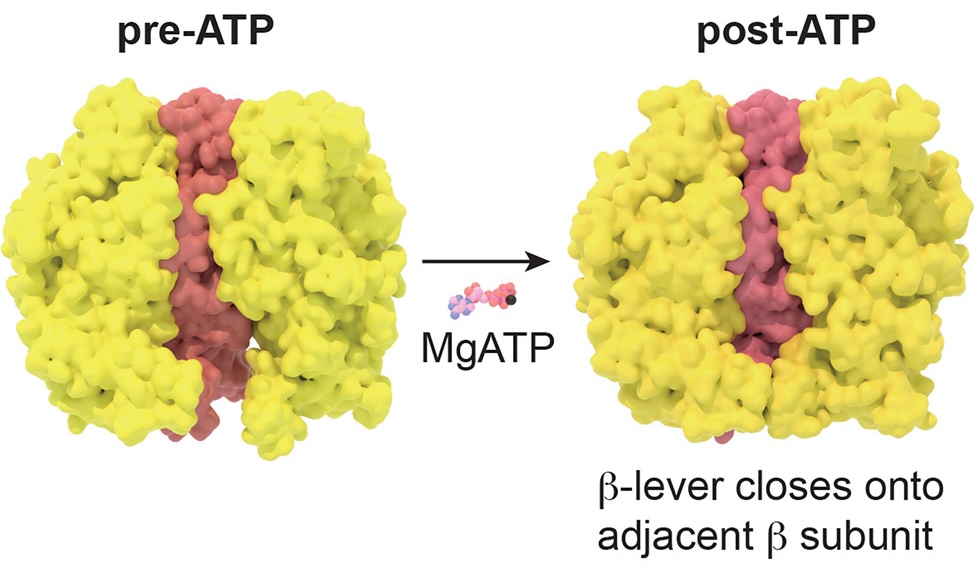

Two conformational states of the F1-ATPase complex. This energy-providing molecular machine found in the mitochondria is a famous example of motion-induced function in molecular biology. Sobti, M. et al.(2024).

Two conformational states of the F1-ATPase complex. This energy-providing molecular machine found in the mitochondria is a famous example of motion-induced function in molecular biology. Sobti, M. et al.(2024).

So what did I actually do?

After learning the essential background theory, I still had to actually do something to show for the rotation! Innovating on a theory or model of physical phenomena is hardwork, but we are lucky as 21st century scientists. We can use our ample computational resources to simulate the results of an experiment that are predicted from a proposed model. We then compare these simulations with real experimental observations, if the the simulations and the observations look the same, your model likely has explanatory power. If the comparison is not very similar, then the model needs some work.

So this was the guiding question of my rotation: Can we simulate diffuse scattering from an ensemble of protein conformers and process it as if it were real data? If so, the simulated data can be compared to real data to see how well our current models of diffuse scattering fit the real thing (recall that I said Guinier’s Equation is the dominant term in the diffuse signal merely due to the presence of distinct conformers, but other terms become not insignificant when there are correlation lengths of and between certain conformers).

James Holton was one of my main scientific mentors for this project, and he had already spent years developing extremely accurate, realistic simulations of diffraction datasets. So my initial task was to understand his simulation scripts and help modify them to account for diffuse scattering due to multiconformer crystals. In order to do so, I needed to familiarize myself with a whole suite of computational crystallographic tools that had been communally developed for decades (CCP4 and Phenix chief among them). I also needed to learn how to read (and write a few lines of!) tcsh command line scripts, James H.’s preferred scripting language. A totally new language to me, but the good news about command line scripting is that there are only so many layers of complexity that can be associated with each line of code. James helped me get set up to work on the LBL Beamline cluster, and after some googling (as well as LLM queries), I was able to understand what I needed to.

James had already scripted the computation of the diffuse scattering from the presence of two conformers, but we wanted to see what the diffuse signal looks like for whole ensembles of proteins, so we modified the script to account for more than just two. That meant parallelization to keep the computation time reasonable. After some great mentorship from James and the reverse-engineering of some of his other parallelized programs, we came up with a working script.1

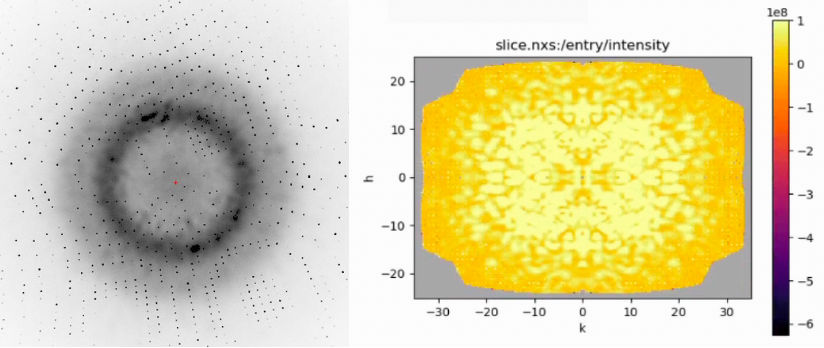

Next step was to process these simulated datasets and see if we could actually extract the diffuse signal from them. In order to do so, I needed to utilize another specially designed software tool, mdx2 - a diffuse scattering signal extractor and processor developed by Steve Meisberger and Nozomi Ando at Cornell University. I recall asking Steve if there was some tutorial that I could access, and he pointed me to an awesome paper written by him and Nozomi that not only linked to a github of step-by-step jupyter tutorials, but also a detailed guide on how to install the necessary Python packages to run mdx2 right in the paper itself! “Whoa!”, I thought. “So that’s what open science is really about.” I was able to get it working with our datasets, and managed to extract the Davinci Dude pattern from one of our simulated diffraction sets as a proof of concept.

Fully simulated diffraction image (left) of the two conformers of 1aho which generate the “Davinci Dude” diffuse scattering featured in James H.’s post. A slice of the extracted diffuse signal in reciprocal space (right) was generated by processing a dataset of these diffraction images using mdx2.

Fully simulated diffraction image (left) of the two conformers of 1aho which generate the “Davinci Dude” diffuse scattering featured in James H.’s post. A slice of the extracted diffuse signal in reciprocal space (right) was generated by processing a dataset of these diffraction images using mdx2.

We moved on to proper ensemble modelling with the SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 macrodomain in its 7kqo P43 crystal form. Using the ensemble_refinement function from Phenix, we created a 200-conformer pseudoensemble (James H. ran the refinement for 3 days to get it), generated an associated diffraction dataset, and processed it with mdx2 to extract the diffuse signal.2

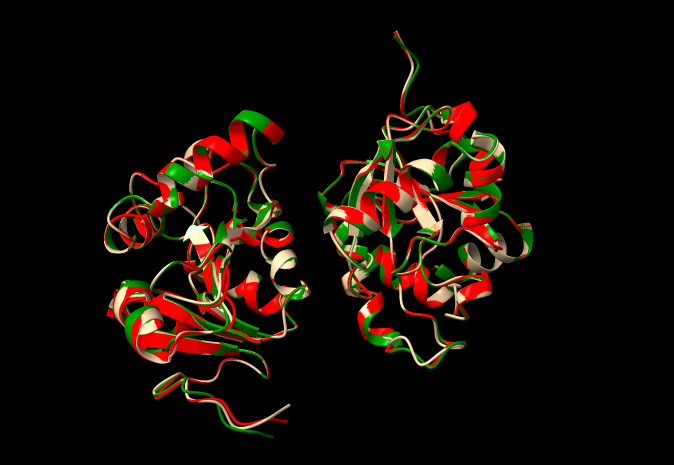

Three representative conformers of the 200-conformer pseudoensemble of 7kqo we used to generate a diffraction image dataset. One is colored green, red, and tan respectively.

Three representative conformers of the 200-conformer pseudoensemble of 7kqo we used to generate a diffraction image dataset. One is colored green, red, and tan respectively.

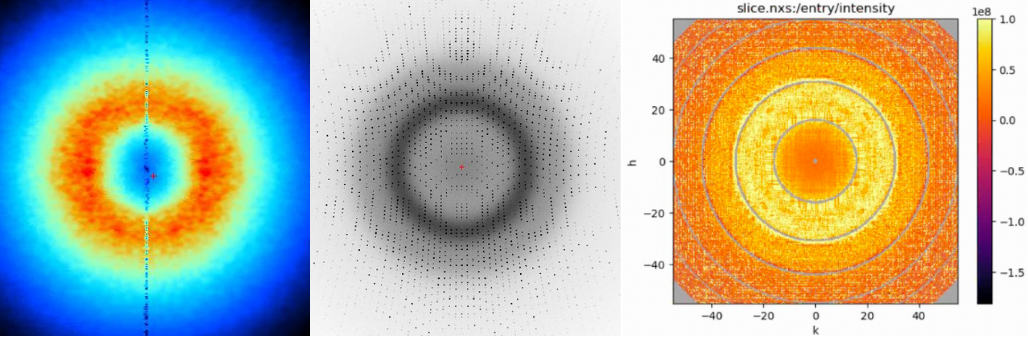

Simulated diffuse scattering (left). Full diffraction image (center). Slice of the extracted diffuse signal in reciprocal space (right). All from the 200-conformer pseudoensemble of 7kqo.

Simulated diffuse scattering (left). Full diffraction image (center). Slice of the extracted diffuse signal in reciprocal space (right). All from the 200-conformer pseudoensemble of 7kqo.

In essense, the result of my summer project is a functional pipeline for simulating the diffuse X-Ray scattering of a multiconformer protein ensemble and subsequent processing of it through mdx2. These simulated signals are now ready to be compared to real signals, and the model of diffuse scattering incremented on. Sadly, my involvement in the story ends here as I need to move on to my next rotation. I’m very grateful for getting to do such awesome science and learning so much under the guidance of James Holton and Jaime Fraser! I would also like to thank the IMSD program and the diffUSE initiative for making this work possible and for helping me get off to a great start at UCSF!

-

Github repo with the scripts used to generate the datasets. ↩

-

phenix.ensemble_refinementwas co-developed between Lawrence Berkeley Nat’l Lab and B. Burnley and Piet Gros from Utrecht University! ↩