The Barrier of Barrier Materials

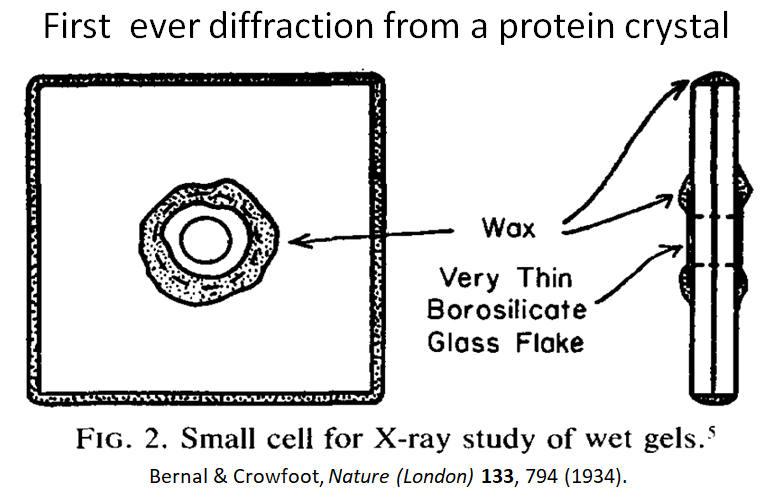

Protein crystals are wet and tiny. Because of this, they dry out in air very fast, and this drying out crushes the lattice and ruins the diffraction. The first person to realize this was Dorothy Crowfoot (who later won the Nobel Prize under her married name: Dorothy Hodgkin). Pictured above is the sample holder she used. Glass flake is an excellent moisture barrier, but it is hard to work with and also glass has relatively high scattering and absorption of X-rays. This scattering makes X-ray background on the detector that can easily bury the faint diffuse-scatter signal from the protein crystal that we are trying to measure. Many different ways of mounting protein crystals have been developed over the years, and each has its compromises. For diffUSE, we will need to really push this technology to make high quality diffuse scatter data a routine undertaking.

The central challenge of window materials for protein crystals is not just the X-ray background, but the permeability. In general, thinner stuff gives you less background, but also dries out the crystals faster. Permeability of a thin film is hard to measure, but the potato chip industry has already done a lot of work on this (Rob Thorne says to google: “barrier materials”). Nearly all polymer-plastic based stuff has the same compromise because plastic is held together by van der Waals forces, and these easily open up to let gas molecules through via thermal motions. A “pile of worms” on the molecular level. Covalent solids, like soda lime glass, are ~1e6x less permeable, but with ~10x more scattering/absorption per unit thickness. I have looked for large sheets of 1-micron thick glass, but nobody seems to make them. You can get broken glass of this thickness and it is very cheap: “glass flake” is a paint additive. I have some, but it is hard to work with.

Recent results in the serial crystallography world have had good results with “SOS” chips, which use 2.5 µm thick Etnom foil (Chemplex). This will have very low background, but variability between crystals has been observed and is still being worked out.

You can also get very low permeability with metal foils. Metallized mylar is a popular barrier material, and you only need nanometers of metal to form a good barrier. Downside is you can’t see through it with optical microscopes, but if you are doing blind, grid-scanning serial data collection then it doesn’t matter anyway. I, however, would like to do the data collection a bit smarter and try to center the crystals in the beam. But that is my bias.

From the X-ray point of view, the background level is very predictable. This is because the cross sections of scattering and absorption depend only on the element, so all you need to do is calculate how many atoms are in the beam and you got your answer. Materials that have been rolled, stretched or pulled will have some orientation bias and therefore fiber diffraction. But, all that does is move the scattered photons around in reciprocal space, the number of scattered photons depends on the elemental composition and little else.

Experience at Cornell has settled on “free mounting” as a solution, but I have found this is not broadly general. About half of all crystals in my experience do not like being exposed to surface tension. The “HARE” chip solution from T-REXX at Hamburg is attractive because the silicon substrate makes a good scatterguard, but you need to surround it with a “rain forest” humidity container. That said, the T-REXX folks have been optimizing it for years. I need to follow up with David von Stetten to talk about the details.

Something else I learned at the most recent Serial Workshop was that people are having good luck with agarose as a carrier for fragile crystals (rubisco). That made me realize: we want whatever is touching the crystals to be softer than the crystals themselves. And I mean “softer” in the Mohs hardness scale kind of way. We don’t want the mount to “scratch” the protein. Agarose also has the advantage that it is easily cast, and cast materials tend to have no fiber diffraction. The trick will be getting it thin and manipulable in a reproducible way.

I want to stress: hardness of the window material is going to be really important. Consider that you not only want the window to be thin, but close to all the crystals. This is because any gap between the windows and the crystal will no doubt be filled with liquid, and that will contribute to the background. Crystals never all grow in exactly the same size and shape, so there is always going to be a compromise between the size of the crystal-window gap for the smaller crystals, and how many of the big crystals are going to be in contact with the windows. If the windows are harder than the crystal, then the crystal “loses”. It gets smooshed. And those were all your biggest crystals.

If we have a layer of soft, amorphous material coating hard windows, then it will move out of the way as the crystal is pressed into it, filling the gaps between them. In this situation the overall thickness of the material in the beam will be fixed from shot to shot, with the only variability being the fraction of the window-window gap that is filled with crystal vs filled with gel. We could then calculate exactly how much gel is in the beam and quantify its contribution to background. I predict this will be a very valuable feature.

Single-crystal windows I haven’t looked at in a while, but I think the SAXS people are the best ones to turn to for such things. We learned early on that diamond windows suck. Too much diffuse scatter from defects in the lattice. They can make “single” crystal diamond, but the mosaicity is pretty poor and the grain boundaries make DS. Beryllium is better. In fact, you want to use etched beryllium. This is because when they roll the Be foil you get tiny rocks and bits of the rollers stuck in the surface. These pits and defects make diffuse scatter. If you dissolve the surface away in acid it makes for a lower background window. These days, of course, they coat all the Be foils with plastic. The plastic makes it a crappier window, but it is more acceptable to our friends in charge of chemical safety.

That said, mica has met with a lot of success as a SAXS window. Ilme Schlichting described to me how to thin it down by pulling off layers with Scotch tape. You look for a color change that indicates it is only a few hundred nm thick. Then it is a good window. Just fragile.

I also have to admit it has been a while since we looked into these things. It may well be that single-crystal diamond has improved over the years. The only way to find out, however, is to buy some and try it. The companies have no idea, but last I checked were interested in the results.

Also, the ultimate thin covalent solid window is graphene. Jeney Wierman tells me she is still traumatized from working with it in grad school, but something she said that stuck with me is that a 1 micron backing material is fine. That also means, I think, that you don’t have to have just one layer of graphene. Ten would probably be ok. Martin Caffrey experimented years ago with graphene-impregnated plastics, but I think he went back to glass. Still. A graphene filled plastic that you spin cast and then UV-set should have a uniform background, and could be very very thin and water tight. You can get “bulk” graphene pretty cheap these days. Something I’d like to test.

@Steve found a paper comparing 10 µm quartz to various polymers and glasses: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6057835/. “Looks promising, provided you avoid hitting a Bragg condition of the quartz.

This reminds me of a big caveat that I’m not sure this work addressed: self-absorption. If all you do is look at the amount of background on the detector, then depleted uranium will look like a good window material: no photons on the detector at all.

Another important principle to remembner is that the scattering cross section of an atom is a fixed quantity. It is independent of the structure of the material it is in: crystal, amorphous, gas, or otherwise. A given number of oxygen atoms in the beam scatters a knowable number of photons. The only thing the structure of the material does is push those photons around on the detector. So, at the end of the day, the only way a window can be “X-ray transparent” is to be thin. And light. And it would be great if it is also cheap and easy to work with.

Looking forward to everyone else’s thoughts and to learning how to do this right!